Names tell us a fair bit about a person.

So it makes sense to remove them from applications, doesn’t it?

Well, what if we told you that bias runs much, much deeper than just names and that to make any real improvements to diversity, something much more radical is required...

What is name blind recruitment?

Name blind recruitment (or blind hiring) does exactly what you’d expect - removes names from candidates’ applications so that they remain anonymous.

Why? Because us humans are prone to unconscious bias.

For the most part, bias isn't something malevolent to be defeated, it's an inescapable part of being human.

We make 1000s of micro-decisions each and every day and so to prevent overload, our brains use two systems to manage them.

- System 1 is much like being on autopilot, using shortcuts to lighten our mental load.

- System 2 is reserved for less frequent, more conscious decision making.

System 1 is extremely useful for navigating our everyday lives.

However, when we fall back on shortcuts and instinct when it comes to hiring decisions, this can result in negative outcomes.

What we call 'unconscious bias' occurs since System 1 relies on subconscious information like stereotypes and past experience to draw patterns.

Given that we're not necessarily in control of which system we're using at any given time, the only way to reduce bias is to design processes that force us to make conscious decisions.

Name bias in hiring

Whether you’re aware of it or not, your name is loaded with information.

For example, it can tell hirers your age (roughly), gender, race or religion.

Although most people wouldn’t like to think of themselves as being biased, it’s natural and pretty much unavoidable.

If we look at how one’s perceived race affects hiring, we can see that those from minority backgrounds are disproportionately overlooked...

In the UK: Inside Out London’s study found that candidates with Muslim-sounding names were 3x more likely to be passed over for a role.

In the US: A 2004 study uncovered that candidates with an African-American name would need an extra 8 years of experience to get the same number of callbacks as someone with a white-sounding name.

In Germany: Another study found that candidates with a Muslim-sounding name, who were pictured wearing a headscarf, were 15% less likely to receive a callback than their white peers.

And then if we look at gender…

In the US: One study of science faculties from selected universities were tasked with rating students’ applications for a laboratory manager position. Faculty participants rated the male applicant as significantly more competent and hireable than the (identical) female applicant.

In Spain: A 2019 study found that men were called back a higher percentage of the time compared to women (10.9% vs. 7.7%).

Key takeaway: a candidate’s name has a very real impact on their chances of hearing back from a job application

Name blind CV example

Your typical name blind CV would usually have the candidate’s name, photo and address removed.

Below, I’ve ‘name blinded’ the CV I was using before joining Applied.

However, name blind recruitment doesn't go far enough.

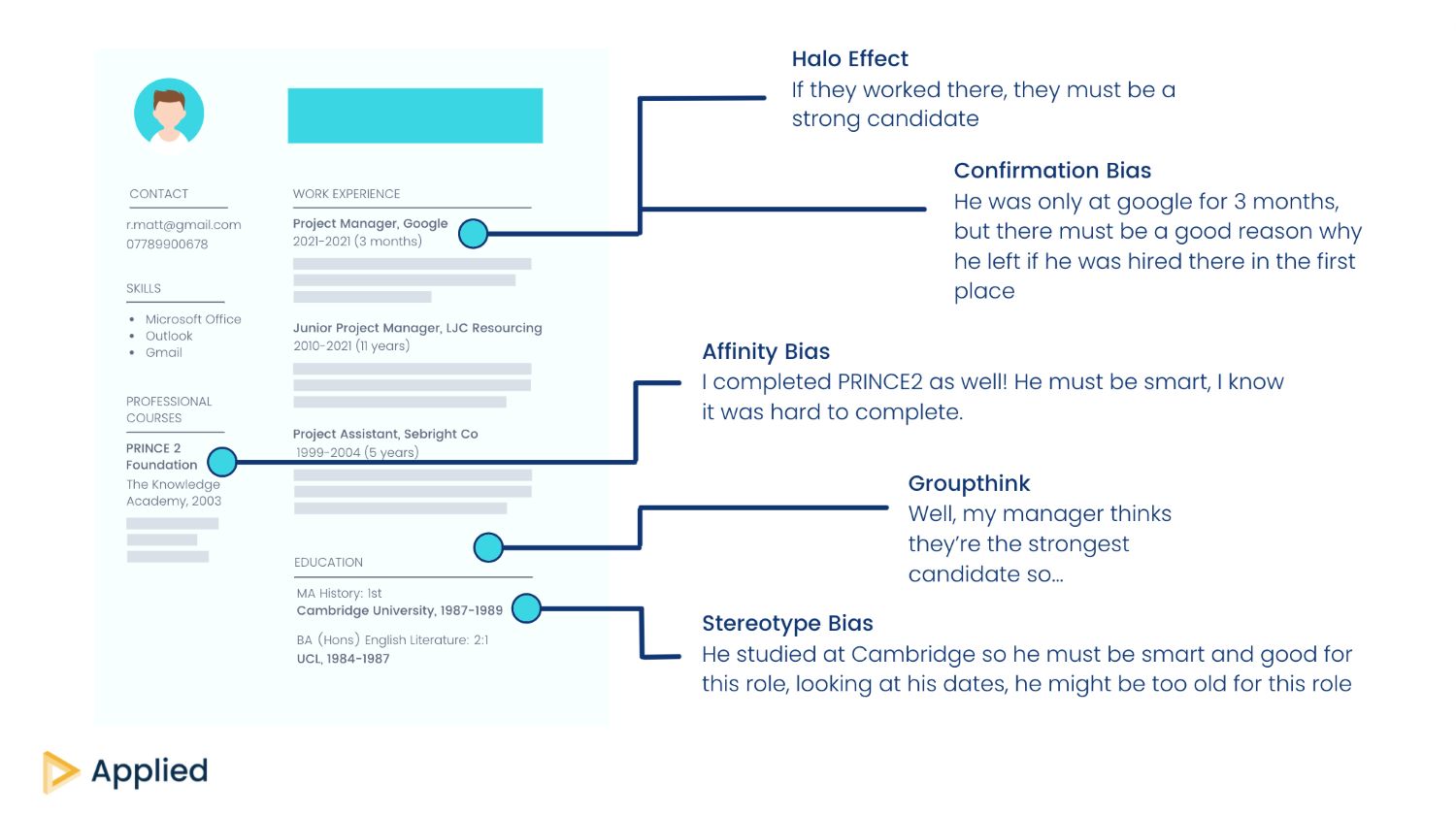

What’s left on a CV (education, experience etc) is still grounds for bias, and doesn’t tell us much about how well someone would perform in the role.

Below, you can see how unconscious bias plays a key role in the traditional CV sift.

Here at Applied, we believe in a blind application process.

And the first step we took towards this was getting rid of the CV entirely.

How does a blind application process work?

Whilst we can all agree that identifying information like names and addresses doesn’t help find the best person for the job, most hirers would probably argue that information around a candidate’s education and experience is absolutely essential.

But as shocking as it sounds - education and experience don’t actually tell us much about a candidate’s real-life ability.

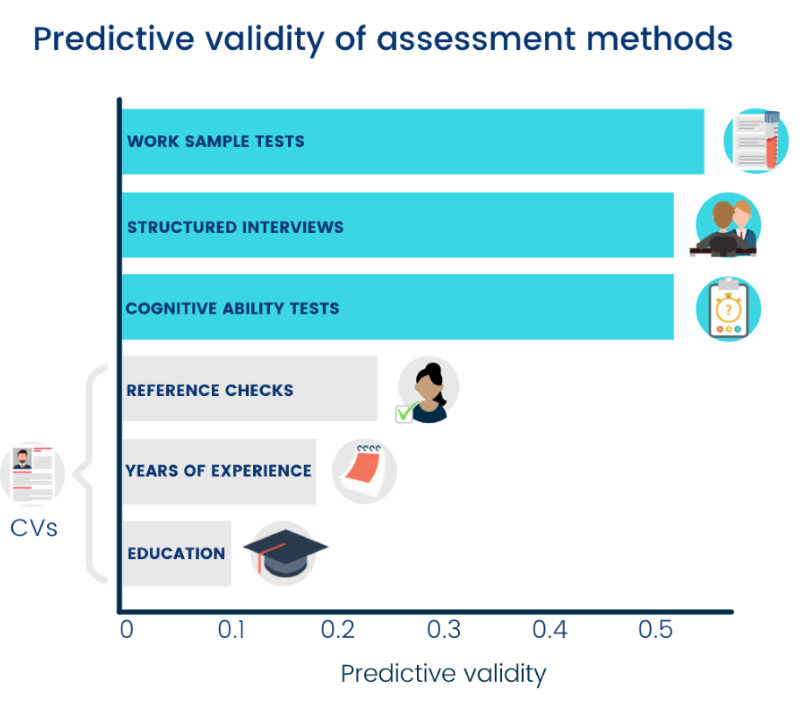

According to Schmidt & Hunter’s landmark metastudy, years of experience and education are some of the least predictive means of assessment.

So, what should you use instead of CVs?

Well, we recommend using work samples (found to be the most predictive assessment by the same metastudy).

A brief introduction to work samples: the key to successful blind sifting

Work samples are interview-style questions designed to simulate a role.

You take a situation or task that would occur in the role (like an event to be organised, a complaint to be managed or an email to be drafted) and ask candidates how they’d approach the task.

The idea is to test skills acquired through experience, as opposed to testing for experience itself.

For a marketing role, for example, you could ask candidates what tests they’d run to find out why website visitors weren’t submitting a certain form.

Work samples are similar to a ‘tell me a time when’ question, except they pose situations hypothetically - since we know that experience itself doesn’t count for much.

If you’d like to learn more about how work samples are used and why they work, we’ve written and spoken about them pretty extensively:

- [Blog post] Use THIS instead of CVs: Here’s our fairer, data-backed CV alternative

- [Resource] Work Sample Cheatsheet

- [Video] Hiring the best: How to create work sample questions

Removing ordering biases from the screening stage

If you’re genuinely passionate about removing bias from your hiring process, the next few steps are crucial.

Even once your blind application process is up and running, there are still ordering effects at play that can influence decision making...

Peak-end effect: both the intense moments and final few moments of an experience have an impact on how we recall and perceive the experience as a whole. Candidates who finish their application strong or have shining moments will likely be unfairly favoured.

Decision fatigue: we make harsher, more risk-averse decisions over time. The more tired we are, the harsher we tend to be. This could mean that candidates scored towards the end of a long day may be judged more harshly.

Recency bias: we can recall recent events far more accurately than ones in the past. When it’s time to shortlist candidates, you’re more likely to choose candidates whose applications were viewed last, since they're the ones you can most easily remember.

We created a simple process for blind sifting to negate the effects of these biases:

- Anonymization: all identifying information is removed from applications.

- Chunking: each candidate’s application is split up into the individual answers - you score them question by question, not candidate by candidate.

- Randomisation: candidates’ answers are shown in a different order for each question.

- Review: answers are scored against the same criteria by three team members (this uses the power of crowd wisdom)

When you put the above steps together, it looks like this:

Using data instead of bias

A blind application process is far more predictive than just name blind recruitment since it uses data to make decisions.

If you’re only removing names and keeping the rest of the process the same, you’re still going to make the same bias-driven decisions, just at a later stage.

Yes, candidates with names that indicate a certain background might make it further in the process, but given that people from more privileged backgrounds tend to get the best degrees and therefore the best experience, diversity gaps will only grow larger unless we make a more drastic change.

So, how can you data-proof your blind sifting process so that decisions are fair and objective?

For each of your work samples (and interview questions, which should also be work sample-esque), create a 1-5 star scale to score against.

Add a few bullet points for what an answer at the top, middle and bottom of the scale would look like.

At the end of the process, simply average out each candidate’s scores to create a leaderboard.

If you’re making the switch to work samples - the most predictive form of assessment there is - then whoever ends up at the top of your leaderboard is the best person for the job, no debating or head-scratching required.

We found that using this process, 60% of the candidates hired ‘blind’ through our platform would’ve been missed in a traditional CV sift (and most likely using just a name blind recruitment process too).

The bottom line: a blind application process is necessary because bias runs deeper than just names

According to Daniel Kahneman’s book, ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, your brain has two systems for decision-making:

System 1: fast, intuitive thinking which relies on rapid-fire associations and mental shortcuts (this is how you walk to work on auto-pilot).

System 2: slow, conscious thinking, used for one-off, more complex decisions (this is how you make important decisions at work).

We make 1000’s of (largely insignificant) micro-decisions every single day and so we need System 1 to pick up most of this slack in order for us to function.

However, we often tend to fall back on System 1 when we should be using System 2.

We use mental shortcuts and intuitive patterns to draw quick conclusions when more conscious thought is required… this is how unconscious bias manifests.

A typical hiring process is rife with unconscious bias since, for the most part, we make decisions and judgements based on ‘gut instinct.’

But the reality is: your gut instinct is biased.

Since we don’t even know when we’re being biased (hence the ‘unconscious’ part), just being made aware of it isn’t enough - we have to change the process that we use to make decisions.

You can’t change human nature (which is why unconscious bias training doesn't work), but you can change the environment in which decisions are made.

The blind sifting process above works because it doesn’t expect people to change how they think and simply stop being biased.

Instead, it simply creates an environment in which bias is impossible.

Applied is the essential platform for debiased hiring. Purpose-built to make hiring empirical and ethical, our recruitment platform uses anonymised applications and skill-based assessments to find talent that would otherwise have been overlooked.

Push back against conventional hiring wisdom with a smarter solution: book in a demo

.png)

.png)