What does it mean for a society to be equal?

Is it all starting from the same point?

Is it all finishing at the same point?

Is it enough to give everyone a fair shot and may the best person win?

Or should we be making sure everyone gets their slice of the pie?

This is, in a nutshell, the essence of the opportunity vs outcome debate - two ways of thinking about equality pitted against each other.

On one side, you’ve got commentators such as Ben Shapiro and Jordan Peterson who, broadly speaking, argue that equality of opportunity has been de-railed by ‘social justice warriors’ in favour of equal outcomes, which is fundamentally unfair.

On the other side, advocates for equality of outcome believe that systemic inequality prevents genuine equality of opportunity, and so the only way to achieve equality is through a more even distribution of wealth - such as diversity quotas and universal income (both of which we’ll come back to later on).

Equality of opportunity advocates are accused of using it as an excuse to maintain the status quo and prevent us from working towards a more inclusive society.

And equality of outcome advocates are accused of pedalling an idealistic fallacy that we can and should all be equal - derailing innovation and economic progress in their wake.

What’s the difference between equality of opportunity and equality of outcome?

Equality of outcome looks to ensure people who are disadvantaged are making gains.

Equality of opportunity looks to ensure that everyone has the same opportunities to make those gains.

So, while equality of opportunity focuses on a level playing field for individual progress, equality of outcome is about overseeing results.

What is equality of opportunity?

At its core, equal opportunity means that people are all given an equal chance to ‘compete.’

The idea is to remove arbitrariness and prejudices from the selection process so that everyone gets a fair shot at success.

The end goal of this playing field levelling is to have a society where the most important (and presumably highest paying) jobs in a given organisation are populated by the most qualified people.

Factors such as race, gender and how well-connected your friends/relatives are shouldn’t play a part in where you end up in life.

In this ideal world, individuals will rise and fall in line with a competitive process - sheer hard work and natural talent being the underlying keys to one’s success since everyone in this society will be able to compete on equal terms.

Here’s how popular self help guru and professor, Jordan Peterson summarises this competition-based view of equality:

"The number one predictor of accomplishment in Western societies is intelligence. What’s the number two predictor: Conscientiousness. Well, what’s that? It’s a trait marker for hard work. So, who gets ahead? Smart people who work hard."

So, it sounds like Peterson is essentially saying that the cream rises to the top. If you’re successful, this is likely due to your intelligence and conscientiousness.

The assumptions seem to be then, that inequality (at least as far as income is concerned) is simply due to these ‘hierarchies of competence.’

Criticisms of equality of opportunity

On the face of it, the most intelligent, hard-working people getting the best jobs seems fair.

But when Peterson talks about ‘intelligence’, what sort of intelligence is he talking about?

IQ (scores of which studies have linked to environmental factors such as family income)?

Emotional intelligence?

Logical-mathematical intelligence?

Interpersonal Intelligence?

The more we learn about behavioural science, the harder it becomes to pin this down.

And even our concept of ‘hard work’ is tied up in historically Protestant values for those of us in the ‘Western World’.

This understanding of equality misses the fact that the socio-economic conditions a person is born into could limit their opportunities - whether that be in terms of education, work ethic or any other factor that might determine someone’s success.

There isn’t necessarily any harm in working towards more equal opportunities, but quotes like those from Peterson above would appear to suggest such equality has already been achieved.

If we look at who actually ‘gets ahead’, it’s not ‘smart people who work hard.’

Wealth is the single biggest predictor of future success, not ability.

According to a 2019 study, smart poor students are less likely to become wealthy by age 25 than not-so-smart rich students.

Co-Author of the study, Education professor Anthony Carnevale, said:

"Young people who are minorities, or from the working class, or low income who are talented when they are young -- they don't make it to the finish line.”

Even if we were to award jobs solely on the basis of merit, how people come to acquire this merit has a lot to do with the privileges they were born with.

Unless we’re all starting the race from the same point (something which would be near-impossible to achieve without serious wealth redistribution), the wealthy will continue to acquire ‘merit’ and fill the best jobs.

At best, equality of opportunity is an unrealistic ideal, and at worst, it’s an excuse to maintain the status quo.

Inequality and ethnicity

Now, let’s take into consideration the fact that those from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to be living in relative poverty (you can see the UK Government’s data here).

Given all of the demonstrable disparities we see between ethnicities, chalking this up to meritocracy is either wilfully ignorant or downright disingenuous.

The evidence is simply so overwhelming that such inequalities cannot be solely rooted in these individuals' lack of ability or ‘get-up-and-go’.

“Hierarchies of competence” do not explain the reality that job candidates from minority ethnic backgrounds have to send 80% more applications to get the same callbacks as a White-British person.

The study above involved sending identical CVs in response to a variety of job ads.

Everything that would indicate ‘competency’ was the same, except for the names of the candidates.

Does this look like equality of opportunity to you?

Let’s suppose we were to remove this bias (which is what we do here at Applied), since 80-85% of jobs are gained through networking, those with the most powerful networks are going to find themselves being offered the best jobs.

Imagine the entire world were to wake up genuinely ‘race blind’ tomorrow, with no ability to perceive one another’s ethnicity.

Would those from minority backgrounds suddenly shoot up the social ladder?

Maybe, at a granular level, some jobs may be offered to candidates that wouldn’t have been before.

Perhaps judicial sentencing would be marginally fairer.

But, on the whole, we’d likely see little change in the overall distribution of top jobs and the wealth that they bring.

Why? Because even if racial biases were to magically disappear tomorrow, some portions of society would still be feeling the legacy effects of racial oppression and slavery.

Some groups in our society have enjoyed more historic privileges than others and would continue to do so because of this, even in a world without racism.

It’s like shooting someone in the leg at the start of a race and then banning leg-shooting halfway through… you’re still going to come last.

While some Mensa-worthy hard workers might successfully climb the social ladder and outperform their peers, these people are outliers and simply don’t reflect the high-level data around systemic inequality.

The reality is that unconscious bias leads to underrepresented groups being disproportionately overlooked, and even if this were not the case, some are too far behind to every catch-up.

What is equality of outcome?

Instead of just looking at the opportunities people are offered, equality of outcome shifts the conversation to where people actually end up.

Put simply, equality of outcome looks to forge a world in which people have similar economic conditions - something which we acknowledge is extremely difficult in a world where its recommended managers be paid around 4x that of those under them.

Rather than looking at how accessible top jobs are for a given group, for example, it measures the representation of that group in these jobs.

If equality of opportunity is a measure of how equal our chances of success are, equality of outcome is a measure of how successful we actually are.

At least on the surface, equality of outcome plugs some of the gaps left by equality of opportunity. It assumes that material success isn’t something only the ‘deserving’ are entitled to, it’s instead something to be equally distributed, since people don’t start from the same point.

Where equality of opportunity (in theory) provides that all start the race of life at the same time, equality of outcome attempts to ensure that everyone finishes at the same time.

A practical example of equalising outcomes is universal basic income - a policy that seems to work in most cases.

In one Finnish study conducted in 2017/18, universal basic income (€650 per month) boosted recipients’ financial well-being, mental health and cognitive functioning, and also modestly improved employment rates.

Another Canadian study found that participants saw improvements in mental health, housing stability and social relationships, along with less frequent visits to hospitals and doctors that lowered the impact on general health services over the three years it was run for.

Criticisms of equality of outcome

Some of the biggest criticisms levelled at equality of outcome are around quotas.

In an attempt to correct historical inequality, some organisations enforce diversity quotas.

They essentially look to fill a set number of roles with people from minority backgrounds.

There are pro’s and con’s to quotas: on one hand they can accelerate change and leapfrog representation of minority groups, although, on the other hand, they can cause tokenism and backlash effects.

Not only are these quotas seen as a superficial solution to fixing racial inequality, but they’ve also come under fire for being ‘unnatural' and ‘unfair.’

The thinking is that if society - or at least the job market - is about competition, it’s natural for there to be winners and losers, provided that these are dictated by competence.

There’s a general assumption that equality of outcome entails handing over jobs and wealth to those who haven’t ‘earned it.’

This also forms the basis of most critiques of universal basic income…

“If we give people money, they won’t be incentivised to work.”

When viewed through this lens, equality of outcome seems oppressive.

In the eyes of its critics, equality of outcome dooms us all to an Orwellian existence in which everybody must be ‘the same’ - one in which our most important, highest paid jobs are filled with unqualified minorities, in their positions by the grace of their identity status alone.

In reality, however, this isn’t what anyone wants.

In fact, painting it in this light is often used as a duplicitous ploy to steer the conversation away from systemic inequality.

Quotas may well not be the best means to secure a more equal society, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be working towards that end at all.

In reality, White, highly-qualified professionals aren’t being snubbed in favour of lesser-qualified Black professionals.

Measuring improvements in diversity doesn’t mean that talented White folks are being unfairly overlooked.

Take the words of CEO Steve Glaveski, for example:

"We create opportunities based on our actions. If I am better networked than you or have more capital to invest, then it might be that I was born on easy street, but it just might be that I worked hard, put in the time, made smart decisions, and am now enjoying the fruits of my labour. The more successful you become, the more opportunities come your way."

Given all we know about the benefits of intergenerational wealth and the vast gap in starting points, for the majority of those born into underprivileged backgrounds, good ole fashioned elbow grease and smart decisions are only going to get them so far.

How would one acquire capital to invest?

How would one build a game-changing network?

It ‘might’ be via hard work and investment of time (which is in itself something not everyone has the luxury of) as Glaveski seems to think it is.

Someone who had a relatively disadvantaged start could plausibly achieve these things.

But generally speaking, if someone of comparative socio-economic privilege applies the exact same amount of grit and nouse, they’re likely to get much further, much quicker.

Here’s what Bestselling Author Angela Duckworth - who write the book ‘Grit’ - says about this:

“If you pit grit against structural barriers to achievement, you may well decide that grit is less worthy of our attention. Caring about how to grow grit in our young people—no matter their socioeconomic background—doesn’t preclude concern for things other than grit.

For example, I’ve spent a lot of my life in urban classrooms, both as a teacher and as a researcher. I know how much the expertise and care of the adult at the front of the room matter. And I know that a child who comes to school hungry, or scared, or without glasses to see the chalkboard, is not ready to learn. Grit alone is not going to save anyone.”

Glaveski does get one thing right - "the more successful you become, the more opportunities come your way."

If some start more successful by default then wealth gaps are only going to worsen over time, which certainly seems to be the case; 70% of the global population are living in countries where the wealth gap is growing, according to a new UN report.

Again, Steve Glaveski may well be a true rags-to-riches story.

But we can’t use anecdotal stories to refute decades of aggregate-level research.

Putting it all together

Right-leaning commentators seem to make the assumption that pushing for equal outcomes means total equality in the material and social conditions of all individuals and demographic groups, which is obviously an unrealistic goal.

Whether this misrepresentation is intentional or not, it gives the impression that hard-working majority groups will be forcibly stripped of their wealth for it to be ‘handed’ to less hard-working individuals, simply because they are from an underrepresented group.

Perhaps the problem is that at least some of those who advocate for equality of opportunity don’t actually want to see it realised at all - and instead are using it to detract from efforts to improve diversity and systemic inequality...

Which may be why equality of opportunity doesn’t seem to take into account the legacy of racism and slavery.

Only now, in 2021, are Black farmers in the U.S being helped out of debt after 100+ years of systemic discrimination and oppression by the United States Department of Agriculture.

And here in the UK, The Windrush Scandal revealed that hundreds of Commonwealth citizens (many of whom were from the ‘Windrush’ generation) had been wrongly detained, deported and denied legal rights - which a report published last year found to be ‘an inevitable result of policies designed to make life impossible for those without the right papers’.

Just because we’re more conscious of inequalities now doesn’t mean groups won’t still be disadvantaged, since they started further behind.

How we see equality at Applied

Although equality of opportunity and equality of outcome are usually pitted against one another, at Applied, our approach is to meet somewhere in the middle.

We set out to build a hiring platform that genuinely levels the playing field so that every candidate gets a fair chance.

However, we also want to ensure this is actually leading to fairer outcomes.

If we don’t measure outcomes at all, how can we know if equality of opportunity has been achieved?

If we see that outcomes are not equal, then we know that opportunities are not yet equal.

Equality of outcome should be the metric against which to measure equality of opportunity, rather than its nemesis.

The Applied platform was designed to tackle just one facet of inequality - hiring.

We don’t claim to solve for deep-rooted, socio-economic inequality but by de-emphasising previous experience and academic backgrounds, we can interrupt a degree of self-perpetuating socio-economic inequality.

We can't provide people with the skills they missed out on developing….

But we can better identify those who do have skills but would’ve been overlooked in a standard process.

60% of candidates hired through Applied would’ve been overlooked via a traditional CV screening.

Why is this? Well, traditional hiring methods rely on assumptions based on proxies that are unfairly distributed (like fancy schools, or prestige past employee brands).

And these proxies aren’t very predictive of ability (the chart below is based on this meta-analysis).

By taking the spotlight off of these proxies, we’re able to identify the best people for the job based on the objective skill set required for that job.

Building a fairer hiring process doesn’t stop there though.

If we de-bias our process and don’t see diversity improve at all, then we’ve changed the process for nothing.

If, for example, female candidates were dropping off somewhere in the process, we’d want to take a closer look at where this is happening to ensure that there isn’t a particular question that favours male candidates (US studies have shown that corporate hirers tend to prefer a masculine style of leadership).

This isn’t shoehorning women into an organisation through enforced outcomes, it’s simply a means of tracking equality of opportunity.

De-biasing hiring instead of using quotas

We believe that by removing bias from the hiring process and using skill (rather than background) testing, you don’t need quotas to improve equality.

We’re aware that some fascinating studies on women’s political representation in India (covered in Iris’s Bohnet’s ‘What Works’) show that quotas can be an effective tool for driving structural change.

However, there’s evidence that quotas can create a considerable backlash, particularly from groups who feel threatened by them - studies have even suggested that the experiments in India might have actually reduced the representation of traditionally disadvantaged ethnic groups.

Implementing a fairer process won’t guarantee a set number of minority background hires like a quota would, diversity will improve over time.

Whilst we tend to stay away from quotas, we do support diverse interview panels and balanced shortlists since there’s evidence that shows these methods make a difference at little to no cost.

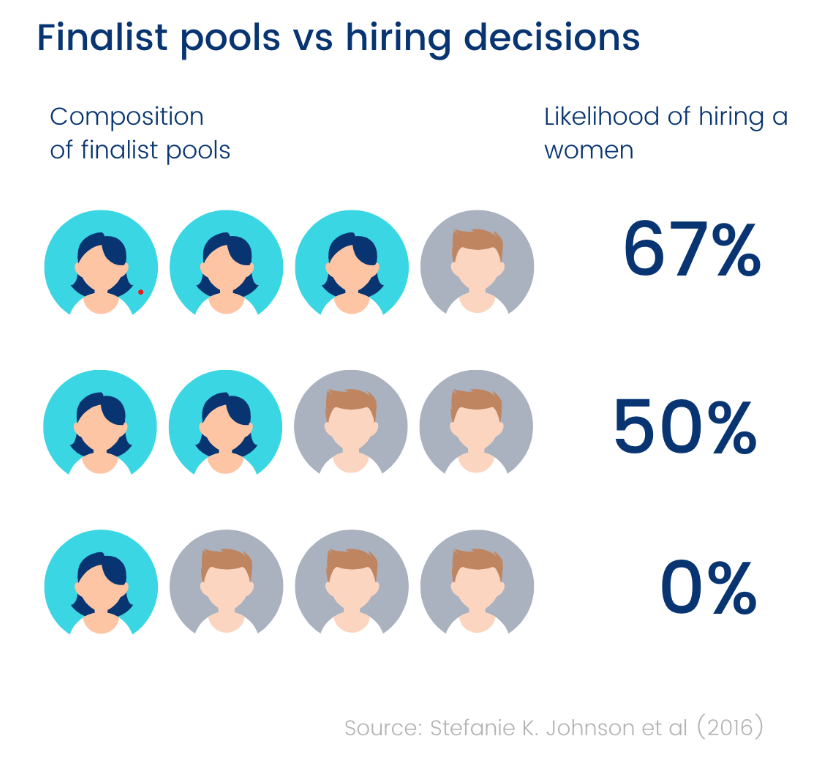

Studies have shown that when there’s just one woman in the finalist pool, their chances of being hired are statistically zero.

So although we wouldn’t advocate for positive discrimination, we do know that without some (minor) intervention some groups’ ‘opportunity’ is near enough non-existent.

Universal design

We’re also part of a general trend toward making systems more accessible by looking at ‘what works’ rather than continuing on a trajectory of copy & paste, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it, design.

Universal design is the concept that buildings, products, environments, systems should be designed to be accessible to everyone, regardless of their age, disability, gender, or race.

While most discussions around universal design are focused on the built environment (think architecture and infrastructure), processes and systems need to be built with a universal focus as well.

It’s why companies like IDEO and entire departments for user research, journey and experience exist now when they hadn’t before.

Out of the 270 underground stations, only 82 have lifts. That means 70% of the underground is inaccessible. Lifts in underground stations don’t just help disabled people - How many times have you helped a parent with their pram or a tourist with their 15 pieces of luggage?

Designs that help one group can help many.

Applied doesn’t just improve the chances for one group, it helps everyone (who has skills/behaviours required) have a fairer chance at getting the job they’ve applied for.

We have been able to prove that by adjusting the barriers to entry for a job and designing a process that ensures genuine equal opportunity, you can impact the equality of outcomes.

Sources

- ‘The Illusory Distinction between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result’, David A. Strauss (1992)

- ‘Defending Equality of Outcome’, Anne Phillips (2004)

- ‘Why Equality of Outcome is a Bad Idea’, Steve Glaveski (2020)

- ‘The Case Against Equality of Opportunity’, Vox (2015)

- ‘Equality of opportunity vs equality of outcome’ Ben Werdmuller (2018)

- ‘What Does Jordan Peterson Mean by “Equality of Opportunity”?’, Ryan Bourne (2018)

- ‘Jordan Peterson Does Not Support ‘Equality of Opportunity’’, Eric Levitz (2018)

- ‘A test for racial discrimination in recruitment practice in British cities’, Natcen (2009)

- ‘Are employers in Britain discriminating against ethnic minorities?’, University of Oxford (2019)

- ‘Jordan B Peterson: Equality of Outcome vs. Opportunity’, Ramble (2017)

- ‘Households below average income: for financial years ending 1995 to 2020’, GOV UK (2020)

- ‘New Survey Reveals 85% of All Jobs are Filled Via Networking’ Lou Adler (2016)

- ‘Universal basic income seems to improve employment and well-being’, New Scientist (2020)

- ‘Generations of Advantage. Multigenerational Correlations in Family Wealth’, Fabian T Pfeffer, Alexandra Killewald (2017)

- ‘The Limits of “Grit”’, David Denby (2016)

- ‘Effect of environmental factors on intelligence quotient of children’, NCBI (2016)

- ‘Windrush scandal explained’, JCWI (2020)

- ‘Slavoj Zizek debates Jordan Peterson’, Manufacturing Intellect (2019)

- 'Curb Cuts' 99% Invisible (2018)

Applied is the essential platform for fairer hiring. Purpose-built to make hiring ethical and predictive, our recruitment platform uses anonymised applications and skills-based assessments to improve diversity and identify the best talent.

Start transforming your hiring now: book in a demo or browse our ready-to-use, science-backed talent assessments.

.png)

.png)