Updated 21/04/21 with new studies and charts

Interview bias: as humans, we’re subject to unconscious biases - mental shortcuts that lead us to make snap judgments and associations. Whilst quick-fire thinking often helps us get us through the day, this type of decision making process can prevent us from making objective and accurate judgments. In interviews, candidates are often overlooked or unfairly favoured based on factors that have nothing to do with their actual ability.

First impressions matter - even though they shouldn’t

Interviews can be a hotbed for all types of bias and as soon as candidates set foot through the door (or pop up on Zoom), your brain starts making associations and misfiring in all sorts of ways.

When you consider the fact that the average CV review takes just 7.4 seconds, you can begin to imagine how quickly we make up our minds about a candidate in an interview. According to one study, roughly 5% of decisions were made within the first minute of the interview, and nearly 30% within five minutes.

This is otherwise known as ‘impression bias’, which describes how the first piece of information we see or learn about a candidate can have a profound knock-on effect. For example, if there is something that immediately causes doubt or suspicion, it can be pretty difficult for a candidate to overcome that initial impression regardless of how they perform thereafter.

Traditional, unstructured interviews are prone to bias

Most interview techniques (at least in my personal experience) turn the process into go-with-the-flow affairs, where the interviewer explores details they think are interesting, with plenty of tangents and general chit-chat.

Whilst hiring managers might believe their trusty recruiter-senses can spot talent from a mile away, this type of interviewing has actually been proven to be one of the worst predictors of actual on-the-job performance.

Another common faux-pas is over-indexing on education and experience.

Probing candidates on the ins and outs of their experience might seem like the most logical line of questioning, but experience (and education) are both fairly weak indicators of real-life skills. In fact, research has shown that these are two of the least effective measures of future performance.

Asking candidates about themselves may also invite interview bias. As we will explore in this article, we are much more likely to reflect positively on people with the same social background as ourselves. While it seems natural to want to build a rapport, even a single characteristic (such as what university they attended) can hinder any attempts at an objective assessment.

Common interview biases to expect from the jump

Stereotype Bias

Stereotype bias is when we assume someone's traits based on their membership of a certain group. Interviewers might start to build a mental profile of a candidate based solely on their race/gender/class etc.

The chart below is from a US study, which looked at how we may perceive those we may characterise as belonging to ‘out-groups’. As you can see, we form ideas about how warm, friendly and competent someone is just from looking at them.

And in another study, participants associated “White” with positive attributes, such as “smart”, quicker than they did for “Black”.

Affinity Bias

We tend to gravitate towards the familiar. Sociologist Lauren Rivera interviewed bankers, lawyers, and consultants - who reported that they commonly looked for someone like themselves in interviews. In other words, when we feel that we have a ‘natural affinity’ with a certain candidate, this can override our ability to evaluate their skills without being biased.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is our tendency to search for information that confirms our preconceptions. If you have a feeling that a candidate isn’t suitable based on their CV (which you probably shouldn’t be using anyway), you’re going to be looking for anything that confirms this from the word go.

Back in the 60s, cognitive psychologist Peter Cathcart Wason discovered that we seek out and attribute more value to evidence that confirms our hypothesis than contradicts it.

Social desirability bias

Everyone wants to make a good first impression in interviews — but this can often present itself in the form of social desirability.

It can happen when candidates are being posed questions of a controversial or sensitive nature and they want to conform to the norm, painting themselves in a favourable light to their potential employer. Although the candidate is not purposefully lying, they may not want to present their opinions in case it affects their success in the interview.

Cognitive biases that affect interview questioning

Halo effect/ Horn effect

Our judgment on one particular aspect of something can unduly influence how we perceive other aspects. In terms of interview bias - a candidate can give a good answer to a question, which then affects how we judge everything else they say. The horn effect is like the halo effect, except in reverse. If our first impression of a person is negative, this can then taint everything else a person says or does afterwards.

Groupthink

Any time we make decisions in a group, we’re open to groupthink, which can come in many forms:

The illusion of invulnerability: If group members liked a candidate personally, they might take risks on them even if they are not right for the role.

Self-censorship: You may find yourself withholding your views and counter arguments due to a lack of openness in the group.

The illusion of unanimity: People assume everyone agrees on a candidate due to silence.

Gender bias in interviewing

There are numerous ways in which unconscious bias keeps women on the backfoot during the interview process. For instance, if the interview panel is composed mostly of men, this provides ample opportunity for affinity bias to come into effect.

One of the main ways in which unstructured interviews play to men’s strengths is that they provide more opportunities for them to sell themselves. We often consider confidence and assertiveness to be a sign of capability, and therefore men’s tendencies to flaunt their accomplishments may reinforce the stereotype that they are more naturally suited to positions of leadership.

A 2019 study carried out by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that when men and women have the same skills tested, men will rate their performance 33% higher than women. Despite performing equally well, women are far more likely to sell themselves short.

Unfortunately, when it comes to gender imbalance in hiring, the statistics speak for themselves.

Multiple studies show that when a man and a woman face off for the same position, the man is often the one to emerge victorious. Research published by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concluded that not only are both male and female hiring managers twice as likely to hire men over women, but when a lesser performing candidate is hired over someone more qualified, two-thirds of the time that weaker candidate is a man.

Interviewers may even phrase questions differently depending on the gender of the candidate. An investigation into VCs found that venture capitalists posed different types of questions to male and female entrepreneurs.

They tended to ask men questions about the potential for gains and women about the potential for losses.

Did you know that many job adverts are also teeming with gender-biased language? If you’d like to find out more, discover how Applied’s gender decoder tool eliminates bias in job descriptions.

How interview ordering can lead to unconscious bias

Even if you were to conduct interviews blindfolded and avoid all background-related questions, there are still ordering effects that prevent objective decision making and result in interview bias.

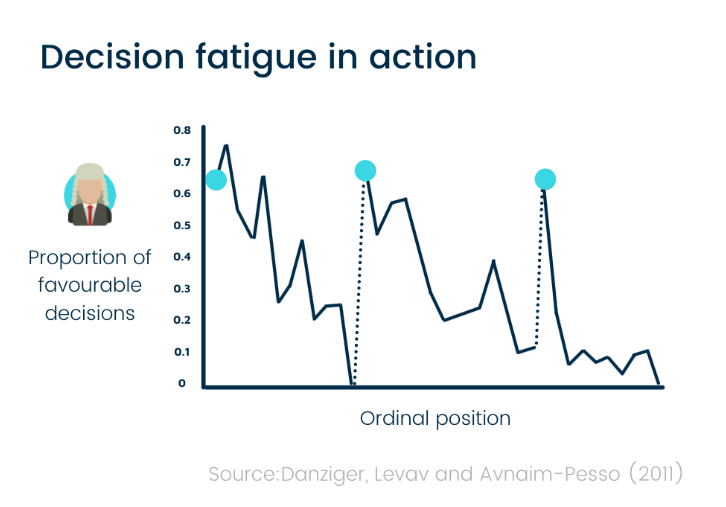

Decision fatigue

Each decision we make fatigues us, leading to harsher, more risk-averse decisions as time goes on. If you’ve got a day of back-to-back interviews, you’ll likely judge candidates more harshly over the course of the day.

A study of Israeli judges found that hasher decisions were made over time, with spikes in favourability after the judges took breaks.

Recency Bias

Recency bias occurs because it’s easier to recall something that happened more recently (our short-term memory only lasts around 20-30 seconds). Therefore you might have a better recollection of your most recent interview than earlier ones, for better or worse.

Contrast Effect

Contrast effect describes our tendency to judge things relative to one another rather than on their own merit. Looking at the image below, the grey square on the right appears to be lighter, when they’re in fact the same shade of grey.

The contrast between different things/people can also make one seem better/ worse than they actually are. If a stronger candidate interviews after a weaker candidate, they may appear more qualified than they really are.

Nobel prize winner effect

The performance of the candidate before you can impact how you’re perceived - this is known as the Nobel Prize Winner Effect.

Why? Because when a Nobel Prize Winner gives a speech they’re usually a tough act to follow. So if the preceding candidate has knocked their interview out of the park, the bar has been raised so high that any misstep is likely to be received more critically than if that person had absolutely bombed.

How can we identify and avoid interview bias?

Use anonymized skills-based testing

At Applied, we anonymise all of our applications so that there is as little chance as possible of hiring decisions being affected by unconscious bias. While you can’t exactly anonymise interviews (without resorting to questionable tactics) you can ask each candidate to take part in what’s called a ‘work sample’. This involves constructing a hypothetical scenario that tests the skills required for the role in question. For instance, we recently used this work sample when advertising for a Community Lead role:

You’ve been invited to be on a panel on hiring & recruitment. You’re the only D&I expert (possibly the only one that thinks it’s important there) in the room. What are your opening lines to the audience to convince and engage them on the subject?

Skills tested: D&I Knowledge, Communication

Each response to a work sample must be anonymised. Then, once you have finished your interviews you can use the results from the work sample to help make your final decision fairly and objectively.

Set up structured interviews with standardized scoring criteria

Free-flow interviews can often veer off course. Structured interviews ensure a fairer candidate experience as every person is asked the same question in the same order before being scored on each question individually.

Instead of experience-based or ‘tell me a time when’ questions, try posing candidates with a task or problem and ask how they’d tackle it hypothetically. The most predictive questions are those which simulate real-life most closely… are there any parts of the job you could get candidates to have a go at?

Here’s how we used this style of question for a Digital Marketer role:

Q1. Below is some fake data to discuss. To meet our commercial targets we think we need to increase our demo requests from 90/month to 150/month. Below are some fake funnel metrics and website GA data. With a view to meeting this objective, talk through the above data and what it might mean.

Q2. What additional data would you need to work out how to meet the objective?

Q3. Given the objective, where would you concentrate your marketing efforts? Is there anything that you would do immediately? Where is the worst place to spend your time, given what you see in the data?

You’ll also want to make sure you have scoring criteria for each question. The first step in fairer interviewing is knowing what good looks like so that you’ll know when you see it.

At Applied, we use a 1-5 star scale.

This means that at the end of each interview round, we can actually build a data-based candidate leaderboard.

Here is the review guide for question one above:

1 star

* No real insights

3 star

* Talks through upward or downwards trends on the data

* Mentions some industry benchmarks and compares the data to them

5 star

* Gets insights from the data

* Understands which ones are the most important (conversion data, traffic, bounce rate)

* Is immediately drawn to the potential problem areas (bounce rate, traffic falling, low conversion from demos)

You may also want to use a scoring rubric that allows you to differentiate between key skills and what we call ‘nice to haves’. Essentially, skills that are an absolute must can be given a weighted score so you can decide which candidate best fulfilled the most important requirements.

Include a diverse interview panel

People are biased… each and every one of us.

No amount of unconscious bias training is going to change that.

There aren’t a few bad apples that we can root out to reduce interview bias - because most bias is unconscious.

However, you can use ‘Crowd Wisdom’ to negate interview bias.

This is the general rule that collective judgment is more accurate than that of a single person.

By introducing multiple interviewers into the process, individual biases should be averaged out, and decisions should be more accurate as a result.

We’ve found that having three interviewers is the ideal number. If your team is large enough, try having a new three-person panel for each interview round.

They don’t all have to have equal input into the questioning, but should all be assessing candidates question-by-question (without conferring).

It’s also worth noting that the more diverse the panel is, the fairer the outcome should be.

Applied is the essential platform for fairer hiring. Purpose-built to make hiring ethical and predictive, our platform uses anonymised applications and skills-based assessments to improve diversity and identify the best talent.

Start transforming your hiring now: book in a demo or browse our ready-to-use, science-backed talent assessments.

.png)

.png)